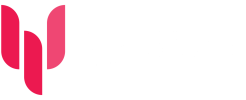

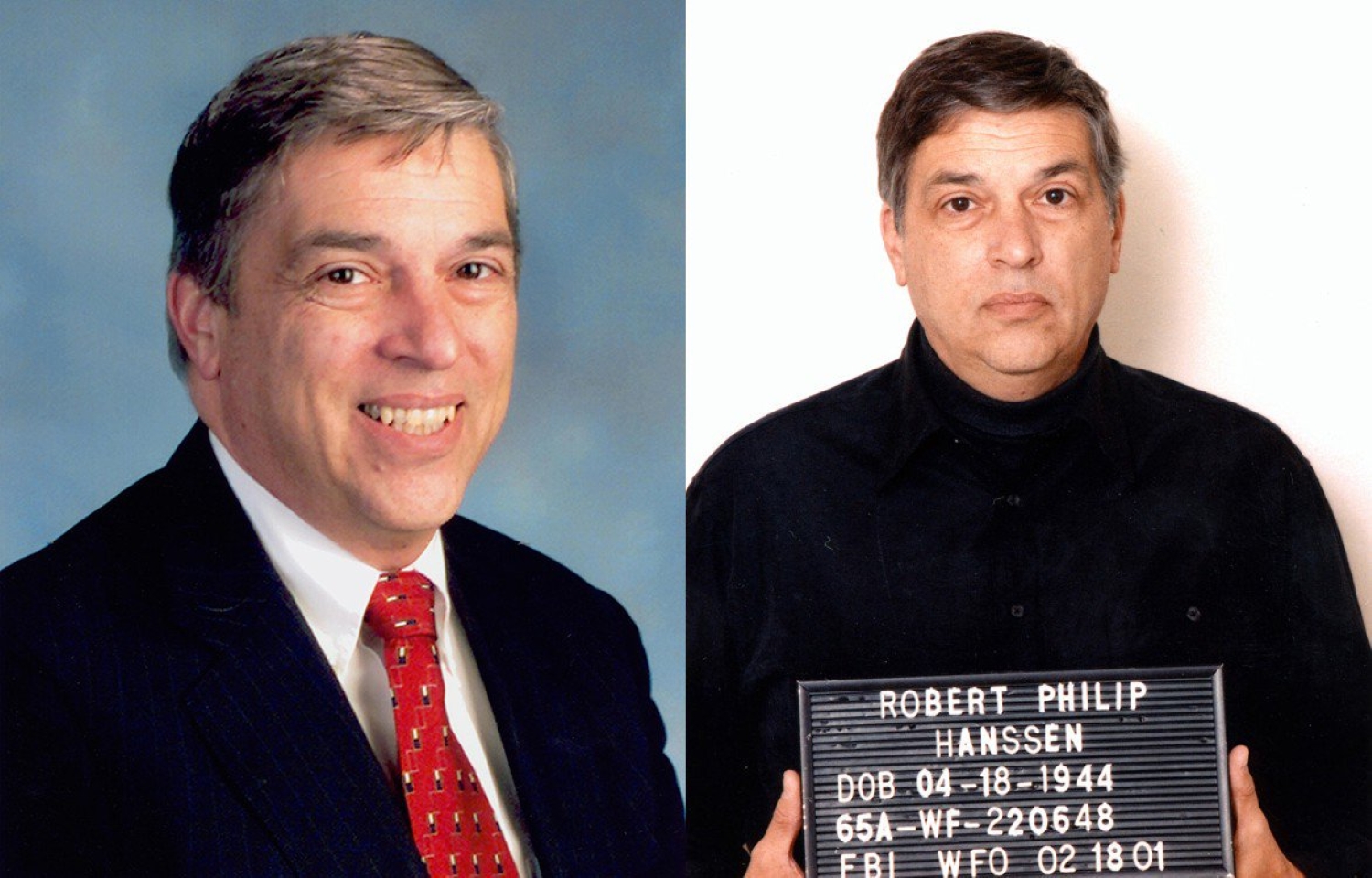

According to prison officials, Robert Hanssen, the infamous FBI double agent who secretly supplied Russia with some of America's most sensitive secrets in the 1980s and 1990s, died Monday in a maximum-security prison.

In exchange for diamonds and hundreds of thousands of dollars, Hanssen offered himself to Soviet military intelligence in 1985, trading government secrets and the identities of US spies in the Soviet and Russian governments.

While investigating Moscow's agents in the United States, he could mask his tracks because he was in the FBI's critical New York counterintelligence bureau, entrusted with tracking down foreign spies.

Did you read this?

On February 18, 2001, he was apprehended while exchanging messages with his Russian handlers in suburban Virginia just outside Washington. He was sentenced to life in jail without the chance of parole.

According to a prison statement, Hanssen, 79, was found unresponsive early Monday in the ultra-high-security US prison in Florence, Colorado, and was subsequently pronounced dead. Hanssen joined the FBI in 1976 after working as a cop in Chicago.

Nine years later, he began working in counterintelligence in the New York City office, where agents spent significant time tracking and recruiting Soviet officials at the United Nations.

Instead, he quickly offered his services to the opposing side under the alias "Ramon Garcia," even his handlers were unaware of his true identity.

When apprehended, he was considered the most destructive mole ever to give US secrets to a foreign government, with hundreds of classified US documents turned over to the Soviets and then to the Russians.

These included US nuclear war plans, software for tracking spying investigations, and the identity of US sources in Moscow, such as Dmitri Polyakov, often known as "Tophat," a Soviet general who passed on his country's secrets to the US between the 1960s and 1980s.

Polyakov was apprehended in 1986 and executed a few years later.

Hanssen collected $1.4 million in cash and diamonds for his betrayals, which are said to have been driven by money and intrigue rather than ideology.

While the FBI and CIA had known for some years that they had a well-placed informant among their ranks, Hanssen was not a top suspect for a long time.

He had a wife and six children, lived on a tight budget, and was close to Washington's orthodox Catholic elite.

With the help of a Russian defector, US investigators eventually focused their attention on Hanssen.

For months, he was discreetly tracked and recorded in his workplace until he was apprehended at the Virginia dead drop.

In exchange for a prosecution agreement not to seek the death penalty, he pled guilty to 15 counts of espionage in May 2002.